|

| Pictured here with Nobel Prize Winner Robert Shiller, fortunate to experience a balmy -7 degrees in Moscow. He also believes that bitcoin is in a huge bubble. |

Despite my view that this is a standard bubble, I tried to buy bitcoin last summer (back at the bargain price of $4,000...), in part because I wanted to see how easy it was to use bitcoin to send money back to the US from Russia. After all, the logic behind bitcoin is that it is a super easy, cheap and fast way to send money. Exactly what I needed. The difficulty I went through in trying to purchase bitcoin only confirmed my worst fears of why I think it is a scam/ponzi scheme. Part of the problems I faced were no doubt specific to me, as a US national living in Russia. Many bitcoin exchanges are country specific, and didn't like my Russian IP address. Others did, but required a lot of information, including a picture of my with an ID, and also a picture of me with a bank statement with my home address (in the US) written on it. I ended up never getting approved, and never got a straight answer from some of these exchanges on why not. Probably, they are just minting money so fast why should they invest in customer support.

But all the information required, even if I had been approved immediately, kind of shoots down some of the logic. If I'm a drug-dealer looking to accept payment in bitcoin, I'm still going to have to provide a lot of information to the exchanges. And, while my troubles may have been unique, bitcoin isn't that easy to use. Your grandma isn't going to be buying groceries or trading bitcoin anytime soon. Indicative of the inconvenience of buying bitcoin, there is a closed-end investment fund which traded on the stock-market that owns only bitcoin, and was recently trading at twice the par value of bitcoin (see Figure below). That is, people who wanted to buy bitcoin in their brokerage accounts were too lazy to cash out their accounts and buy bitcoin directly, so they paid double the price to avoid the hassle.

In addition, the fees associated with buying bitcoins in Russia using rubles, sending them to myself in the US, and then converting them back into dollars are at least an order of magnitude larger than just buying dollars using my currency broker, and then sending money to myself directly. The total cost of my normal fees for doing this set of transactions run about $25 for a $10,000 transaction using the banking system and my currency broker. By contrast, I'm told the bitcoin broker in Russia charges 3%, and one in the US (Coinbase) charges 2% per transaction (maybe this is now 1.49% for Coinbase users in the US, although it looks as though they charge 4% to fund an account using Visa/Mastercard), plus whatever the bitcoin miners charge (perhaps .2%?). Even the miner's fees are calculated in a super non-transparent way. It's probably that way for a reason.

Theoretically, some other problems with bitcoin is that there is free entry. Anyone can create an infinite amount of cryptocurrency out of thin air. The marginal cost is zero. The saving grace is that there are network effects -- a currency becomes more valuable the more people that use it, and so it will be tough for other cryptocurrencies to displace bitcoin. However, that can't explain why there are thousands of cryptocurrencies with huge market caps. Only 1-2 of these will ultimately be the victor, and bitcoin is likely to be one of them.

Another issue with bitcoin/cryptocurrencies long-term is that if they ever did replace actual currencies in everyday transactions, governments could really lose out. The Federal Reserve would lose control over monetary policy, for example, and to the extent cryptocurrencies enable drug smugglers and hackers and others to evade the authorities and paying taxes, this should be something which governments will have a real interest in illegalizing. Thus, there is no endgame where bitcoin replaces the US dollar, the Chinese Yuan, or the Euro as the primary currency of a major economy. It is simply too volatile, and there will be nothing to stabilize its value.

The real economic argument for bitcoin is not that it actually provides cheap transaction fees, but rather that it is a really good scam/meme. It's techy, it's complicated, and few people understand it. Those who spent the time to learn how it really works then become part of the cult and evangelize over it. It could be compared to the spread of a religion: If many people very fervently buy into it, it could be a bubble that lasts a long time. This is the optimistic case for bitcoin. There are a group of Japanese in Brazil who went to their graves believing that Japan didn't lose WWII, and it was just US propaganda that suggested otherwise. The bitcoin true believers/dead-enders may hold bitcoin until the day they die, giving it a positive value for a long time to come.

Or, it could be more like the spread of a disease (I'm stealing this from Robert Shiller). To grow, the disease needs a lot of new people to infect. Once about 20-30% of the people are infected, it's growth will be at a maximum. But, over time, there are fewer and fewer new people to infect, as most people have had the disease, and the rate of new infections crashes. Bitcoin may not be so different -- the early adopters buy in, sending the price up. The higher price means more news, and is a positive feedback loop as the mainstreamers start to buy. Doubt creeps into the minds of naysayers, who might have believed it to be a scam initially, but now see the price soaring, against their predictions.

Usually the moment to sell is after almost everyone who is a quick adopter has already adopted, the median person has too, and the moment at which people who are typically late adopters start to invest. At that point, the economy will run out of suckers, and the price will start to stagnate and fall. Legend has it that Joe Kennedy sold his stocks in 1929 after a shoeshine boy started giving him stock tips. An older family member of mine was day-trading tech stocks in the 1990s, and then bought a condo in Florida in 2006. This person is my bellwether.

Given this may be a reason to buy in the near term, before the late adopters get wind (and, damnit!, why didn't I realize early on that this was a good scam!), be warned that just as the positive feedback loop works well on the way up, and it can work in reverse on the way down. A few bad days, and panic selling can ensue. Once it crashes, a generation of people could be so turned off by crypto they'll never touch it again.

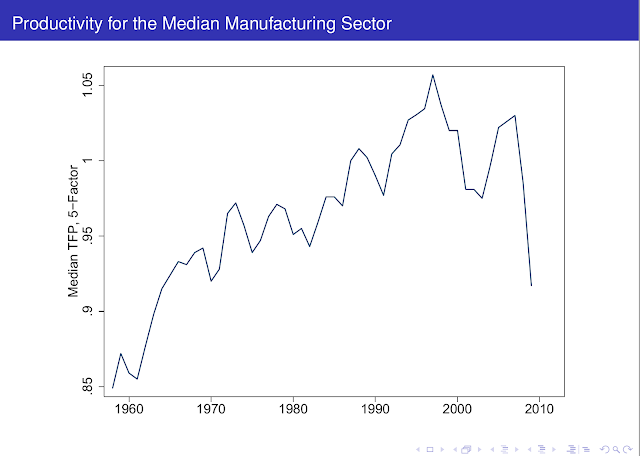

What crypto does is settle the debate over whether fundamentals drive stock prices and exchange rates. I gave a talk at LSE a few weeks ago on my research on exchange rates and manufacturing, and someone stated their belief that exchange rates are driven by fundamentals (monetary policy) and so it was monetary policy which drove my results and not exchange rates, per se. However, as we see with bitcoin, which isn't driven by any kind of fundamental economic value, as it pays no dividends and has high transaction fees, bubbles can happen and markets aren't that efficient. (OK, even if you believe in bitcoin, how much do you believe in Sexcoin, Dogecoin, or "Byteball bites", the latter of which has a market cap of a cool $187 million...) There is never going to be a day when everyday people use "byteball bites" to buy groceries.

It also shows another reason why governments might want to tax windfall profits or large capital gains at a higher rate. Those profiting from cryptocurrency are incredibly lucky. Their "investments" don't leave any reason to deserve favorable income treatment relative to wage income. Stock market earnings are similar. Luck is involved just as much as skill.

Lastly, though, let me state my agreement with others that government-sponsored electronic currencies are probably a thing of the near future. If an electronic currency allows every transaction (or most transactions) to be traced by the government, it can cut down on illegal activity, narcotics, and tax evasion. A government could really very easily broaden the tax base, and raise more revenue while cutting taxes on law abiding citizens. This will probably help developing countries (like Russia) where tax evasion is rampant the most. I guess this will happen soon. Greece should do this and leave the Euro system (but not the EU!). Obviously, a digital currency also solves the problem of the zero lower bound on interest rates, reason enough to do it. Were I the Autocrat of All the Russians, I'd have implemented this already.

In any case, I don't want to give anyone investment advice. I have no clue what will happen to the price of bitcoin, although that should be a warning. I hope none of my friends miss out on the huge boom as bitcoin goes from $10,000 to $100,000 just because they read this. Just be for-warned that what goes up must come down. If you do ride the wave up, think about taking something off the table and try to remain diversified. (That goes for the US stock market too, which also now looks quite overvalued...) Once your parents start to buy bitcoin, that's probably a good time to cash out.